A Copy of a Copy of a Copy: the Story of FDA Medical Device Clearances

March 10, 2024

11 min read

Motivation

Back in the Fall of 2022, I watched the 2018 documentary The Bleeding Edge1, which investigates the FDA's medical device clearance process. I was surprised to learn that for many devices, clinical trials are not required.

The documentary scrutinizes the FDA's 510(k) clearance process, through which some devices can be fast-tracked for use if they are "substantially equivalent" to an existing device, even without a clinical trial.

Several of these devices even led to patient injuries including bleeding, organ puncture, and even cobalt poisoning.

Although the documentary led to some of these devices being pulled off the market 2, I was curious whether similar devices might exist that haven't gotten the publicity yet. However, after some research, I found that the public data available was insufficient to answer my questions.

So, I put on my detective hat and began investigating the data that was available.

Before I dive into the details, it's important to know a little backstory on how medical devices get regulated in America.

A Brief History of Medical Device Regulation

Before 1938, there were a few laws regulating food and drug quality, but the Federal government did not have much authority to enforce them.

In 1938, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act3 was signed into law, granting the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) much more authority and requiring a pre-market review for new drugs to verify safety and effectiveness.

Until 1976, however, medical devices were not regulated by the FDA. A 1976 amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act extended the FDA's jurisdiction to include medical devices. The amendment established 3 classes of medical devices: Class I, Class II, and Class III, ordered by the level of risk to the patient.

For example, latex examination gloves are a Class I device (low risk), but a pacemaker is a Class III device (high risk). Devices like joint implants and tooth fillings fall somewhere in the middle, at Class II.

There are a few pathways for device manufacturers to begin selling their devices.4 I won't get into all of them, but the main pathways are PMA or 510(k).

PMA

Premarket Approval (PMA) is a more rigorous process which requires a clinical trial to demonstrate that the device is safe and effective. All class III devices must go through this approval process to be legally marketed. However, only 1% 5 of medical devices are cleared through this process.

510(k)

The 510(k) process provides a faster route to marketing a new device. New devices are allowed to be marketed if it is shown that they are "substantially equivalent" to a legally marketed device, and are either Class I or Class II. This process does not necessarily require a clinical trial to demonstrate safety or effectiveness, the applicant need only show that the device is equivalent to something legally on the market already. This marketed device is referred to as the "predicate" device.

The predicate device could itself have been allowed through a few pathways. The predicate could be a pre-amendment device, meaning something that was on the market before 1976 and grandfathered in. It could also be a device that received Premarket Approval.

Lastly, the predicate device could itself have been cleared by the 510(k) process.

This last detail is what sparked my curiosity.

A cleared device could be equivalent to some long chain of 510(k) cleared devices, without any of these devices requiring a clinical trial!

This was not how I expected medical devices to be cleared for the market.

Wait it's just a graph?

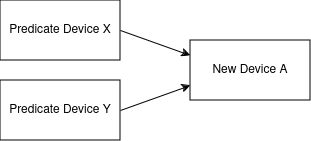

This is where I had to dust off my computer science knowledge. We can model this as a graph, where each 510(k) submission is a node, and the predicate relationship is an edge. A device may use multiple predicates in its application.

For example, if device A has predicate devices X and Y, the graph might look like this:

We could imagine this extending out across dozens or hundreds of devices in a 510(k)'s "ancestry".

Finding the data

The next problem I had was how to find the data. There were two sources for FDA 510(k) data that I found: The Premarket Notification Database6 and even better, the OpenFDA API dataset7, which provided a fairly comprehensive dataset as a single JSON file.

"Great!", I thought, this data will be perfect for mapping out predicate devices as a graph.

Except for one issue: the data does not include predicate devices.

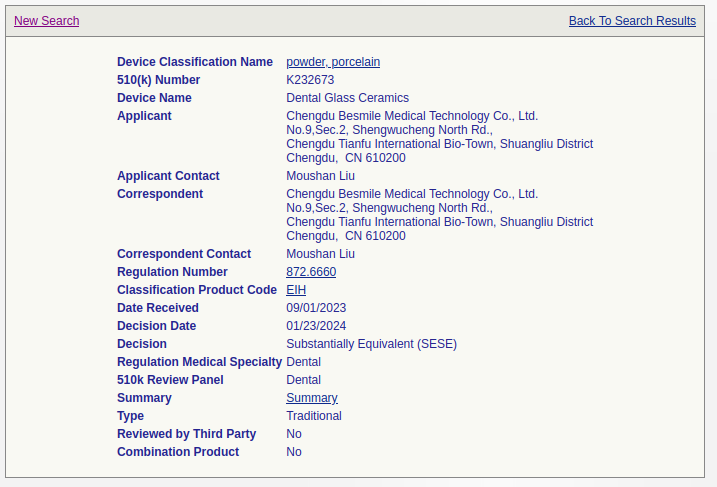

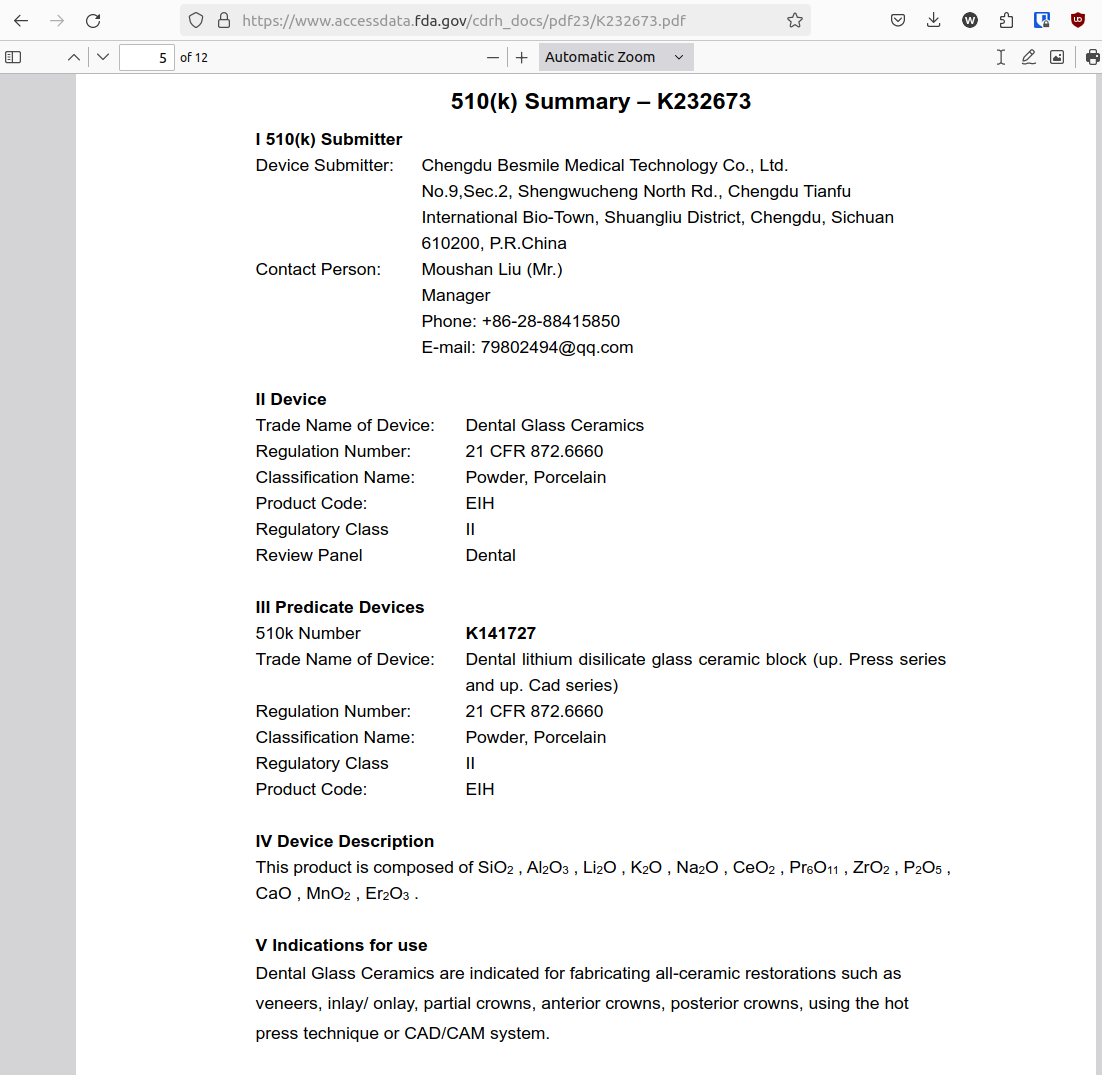

As it turns out, the only way to find the predicates of a given device is by checking if a PDF summary of the application is available, and if so, examining it manually. These PDFs are completely free-form and do not even have a standardized template.

As of March 2024, there are 85,791 510(k) applications with summaries available, so doing this manually was just not going to work.

Another problem is that the FDA does not provide a single dataset containing all of these PDFs, as they do with the API data.

So, left with no other option, I decided to scrape the FDA's website to download all 85,791 PDFs.

Scraping PDFs

I used Python's BeautifulSoup library to scrape the database. In the database, each entry contains a link to the summary PDF file.

The "Summary" link goes to a PDF file hosted on the FDA's website.

With beautifulSoup, it was fairly simple to search for the word summary to find this link:

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.data, features="html.parser")

summary = soup.find("a", string="Summary")

url = summary.attrs.get("href")

Once I had this link, I just downloaded each PDF and stored it locally.

Being a polite scraper

The FDA's robots.txt includes the following lines:

Hit-rate: 30 # wait 30 seconds before starting a new URL request default=30

Visiting-hours: 23:00EDT-05:00EDT #index this site between 11PM - 5AM EDT

Which means to be polite (and not get blocked), my scraper can only run between 11 PM and 5 AM (6 hours), and can only make a request every 30 seconds.

This means we can only scrape 6 * 60 * (60 / 30) = 720 files per day. So it took 85,791 / 720 = 119 days to scrape every PDF.

To accomplish this, I ran the scraper on a $6/month DigitalOcean droplet and let it go to work, then I checked back in 4 months and copied the PDFs to a local directory.

Parsing Predicates

Now that I had all the PDFs, the next problem was parsing them.

With the pypdf Python library, it was easy to grab the embedded text from each document.

Once I had the embedded text, I just ran a regex match for strings with a K followed by 6 digits like K123456.

There were some common variations like using a # or a space after the K, which I also matched.

However, I hit another issue with older summary documents. The older PDF documents did not have embedded text, because they were often scanned PDFs, not digital. Using tesseract, I ran OCR (Optical Character Recognition) on the PDFs where I could not find predicate device IDs. This worked pretty well, but the OCR quality was fairly low.

Finally, for documents that were still missing predicates, I manually entered them using a Python script to display the PDF and accept the ID as input.

Sometimes this required searching for the predicate manually by name in the database.

Out of the 85,791 devices with summaries, I was able to find predicates for 63,389 (74%) devices.

Sometimes the summary would omit the exact predicate used or would provide a name that was not specific enough to identify a 510(k) application. These I ignored.

Storing the data

I stored the predicate data in a simple SQLite database with a table containing two columns:

node_to and node_from. This allowed me to run some simple queries on the data, and also

join it against the device data found in the API dump.

Answering some questions

How many predicates does a device have on average?

Let's fetch the edges from the database and load them into a networkx graph.

I'm deliberately ignoring devices that are missing predicate information. I only care about the devices where we do have ancestry available.

import networkx as nx

import sqlite3

con = sqlite3.connect("../scripts/devices.db")

cur = con.cursor()

cur.execute("SELECT node_from, node_to FROM predicate_graph_edge;")

all_edges = cur.fetchall()

g = nx.DiGraph(all_edges)

We use a DiGraph object, which stands for Directed Graph, because

each edge in our graph is directed.

Device A being the predicate of device B does not imply that

B is the predicate of A.

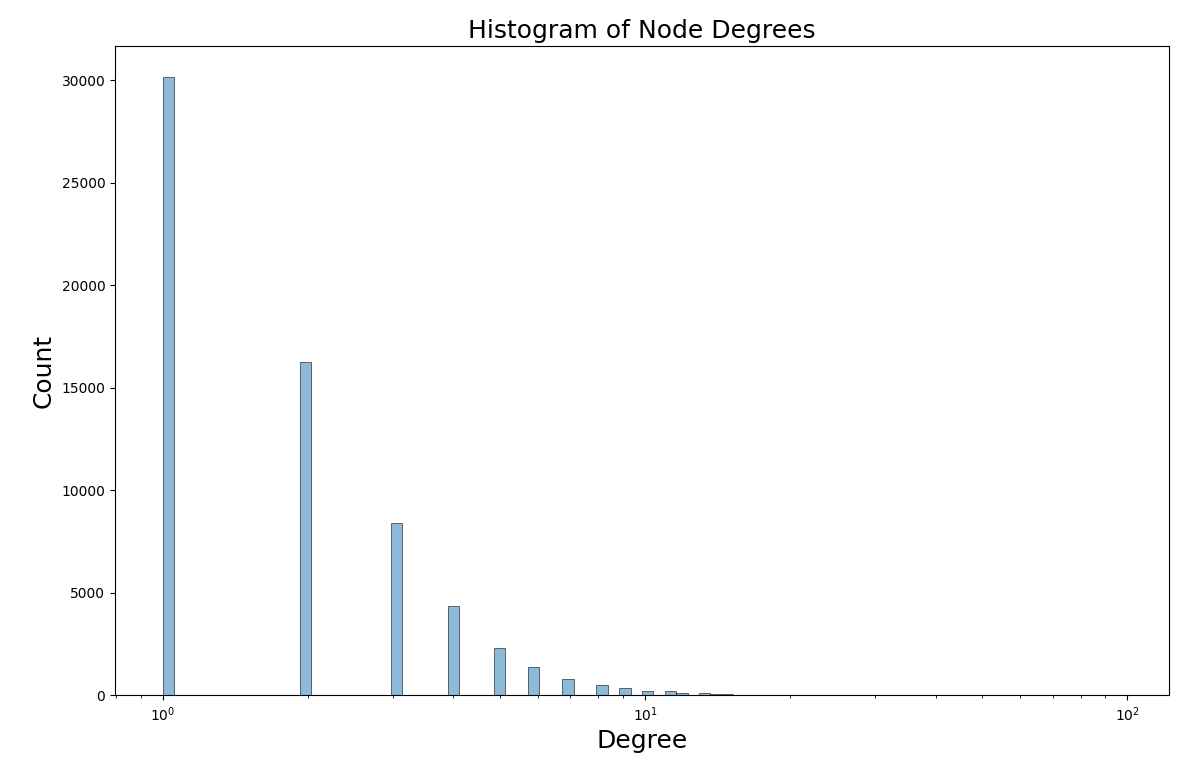

We might wonder how many predicates, on average, a device has. In graph theory terms this is called the degree of the node, in other words, the number of neighbors a node has connected to it.

Now we can calculate the average degree of a device:

print("Average degree:")

print(sum(map(lambda x: x[1], g.in_degree())) / len(g))

Average degree:

1.7794783986208664

We can also calculate the median degree:

print("Median degree")

print(statistics.median(map(lambda x: x[1], g.in_degree())))

Median degree

1

The average is skewed higher than the median because the degree follows a power law distribution, which we can see by checking a logarithm-scaled histogram of the degrees.

Setting up a website

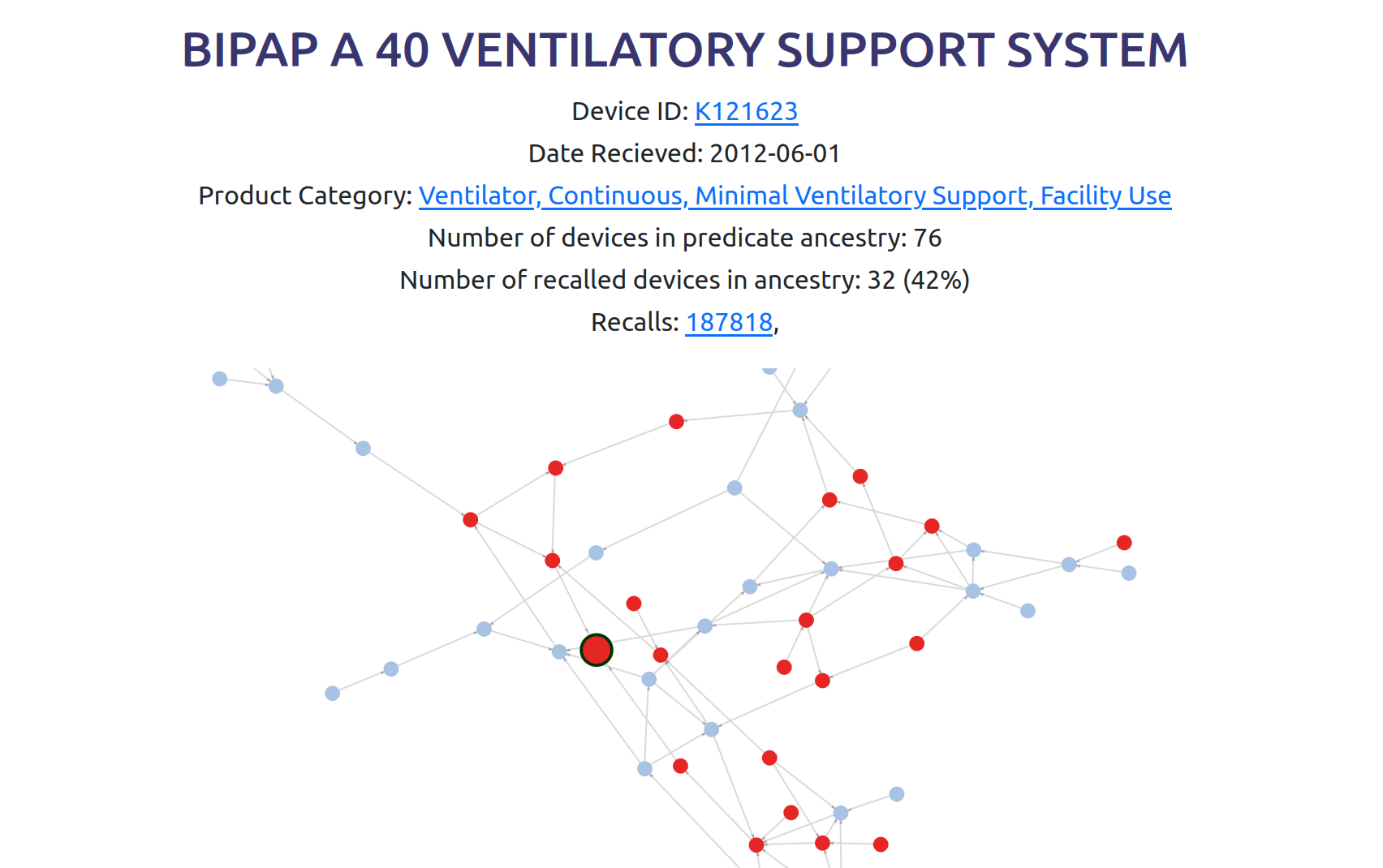

To make this data more accessible to anyone, I set up a website to visualize it: 510k.fyi

The website allows you to find a device and see its predicate device ancestry as a graph. This screenshot shows the recently recalled Philips BiPAP CPAP machine8 which resulted in 561 deaths.

To see this interactive graph, click here.

The website is open source, free to use, and requires no account. Check it out!

The tech stack for this website is:

- Python and FastAPI for the backend

- SQLite for the database (although I plan to switch to PostgreSQL later)

- NextJS and React for the frontend, along with react-force-graph for visualizing the data

The most interesting part of this setup is using SQLite instead of a graph database. I was thinking a dedicated graph DB like neo4j might be needed, but the performance so far with SQLite has been great.

My schema looks like this:

CREATE TABLE predicate_graph_edge(node_from TEXT,node_to TEXT,

FOREIGN KEY(node_from) REFERENCES device(k_number),

FOREIGN KEY(node_to) REFERENCES device(k_number),

PRIMARY KEY(node_from, node_to));

In other words, the predicate_graph_edge table holds all edges (relationships from predicate devices to the new device).

These edge columns are also foreign keys to the device table, which represents the nodes in our graph.

Using a recursive CTE, we can query for all the predicate ancestors of a given device. This query will return all the edges.

WITH RECURSIVE ancestor(n)

AS (

VALUES(?)

UNION

SELECT node_from FROM predicate_graph_edge, ancestor

WHERE predicate_graph_edge.node_to=ancestor.n

)

SELECT node_to, node_from

FROM predicate_graph_edge

WHERE predicate_graph_edge.node_to IN ancestor

But we also want the node data, so we can embed this in a subquery and JOIN it on the device table (and the recalls table).

SELECT device.k_number, recall_id, recall.reason_for_recall

FROM (

WITH RECURSIVE ancestor(n)

AS (

VALUES(?)

UNION

SELECT node_from FROM predicate_graph_edge, ancestor

WHERE predicate_graph_edge.node_to=ancestor.n

)

SELECT node_to, node_from

FROM predicate_graph_edge

WHERE predicate_graph_edge.node_to IN ancestor

) ancestry

JOIN device ON ancestry.node_from = device.k_number

LEFT JOIN device_recall ON device_recall.k_number = device.k_number

LEFT JOIN recall ON device_recall.recall_id = recall.id;

The ? in this case would be replaced with the root device in question.

For a nontrivial query (327 rows),

Using SQLite's .timer on command, we can see how fast the query is:

Run Time: real 0.155 user 0.135287 sys 0.019959

You can also see this data visualized here

Source

The source code for the scraper, website, and data analysis is all available under an open source license here: https://github.com/wcedmisten/fda-510k-analysis

Footnotes

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Food,_Drug,_and_Cosmetic_Act ↩

-

https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/device-advice-comprehensive-regulatory-assistance/how-study-and-market-your-device ↩

-

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/227466 ↩

-

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm ↩

-

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/fda-sleep-apnea-philips-recall-cpap/ ↩